Sharing stories with... Raghav Kumar and the Tiny Farm Fort

Nestled in the remote mountainside forests of Rishikesh in northern India, the Tiny Farm Fort stands as a testament to nature's creativity and the power of community. Acknowledging the rapid decline in a centuries long tradition of using natural materials, architect brothers Raghav and Ansh Kumar formed the Tiny Farm Lab with the mission to challenge a homogenous future dominated by fired red bricks, concrete and steel. The result is a Tiny Farm Fort; a small curvaceous cob house with a deep connection to nature.

ARCHITEXTURES Editor-at-large Vanessa Norwood spoke to Raghav Kumar about his ethos of building through care, community and conscious materials, all powered by a serious amount of dancing!

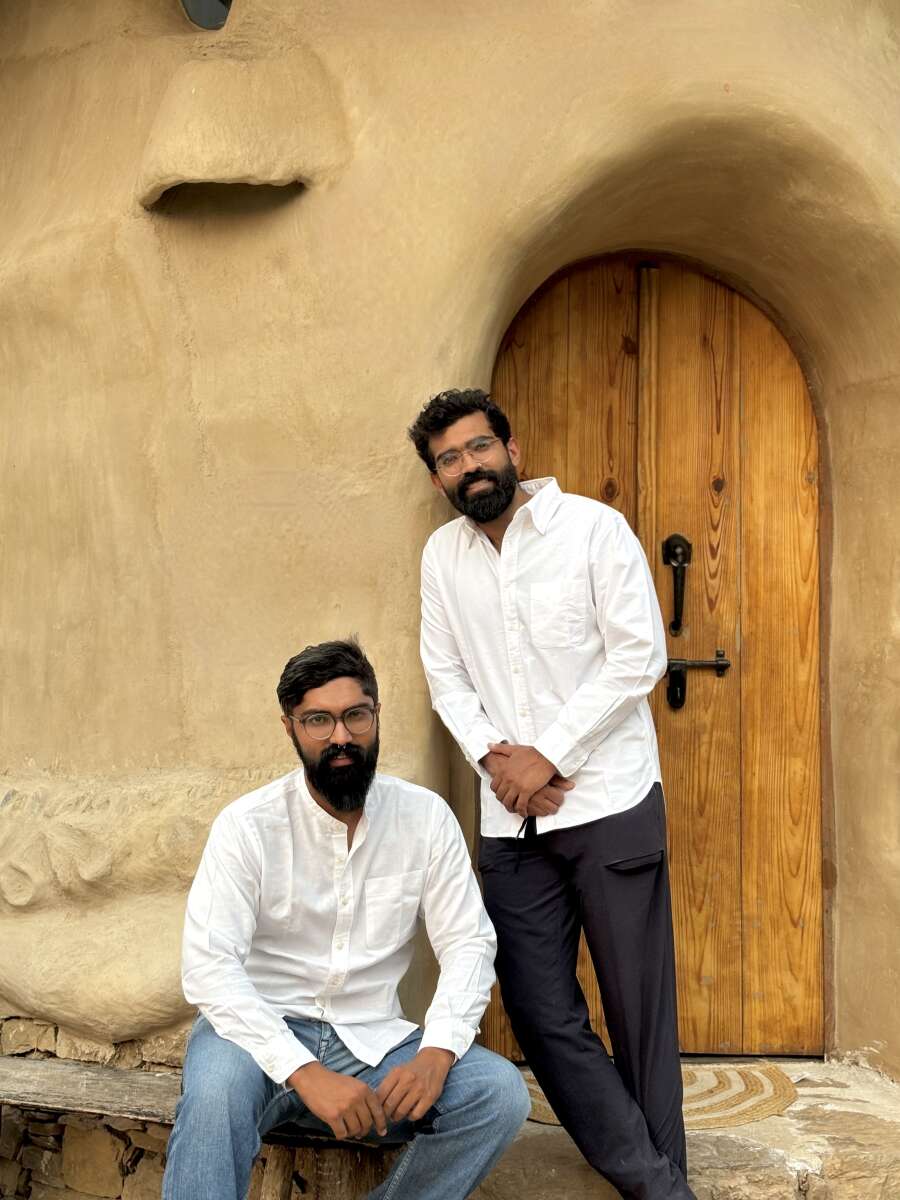

Left: brothers Raghav and Ansh Kumar. Image credit, Aishwarya Lakhani. Right: Close up view of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Left: brothers Raghav and Ansh Kumar. Image credit, Aishwarya Lakhani. Right: Close up view of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Vanessa: You went from four years of working in corporate architecture for a German company in India to living in a remote mountain village in northern India. What brought about such a radical move and how did you come up with the idea to make the Tiny Farm Fort?

Raghav: I quit my job when my hair turned grey! I was building a platinum rated green building that ticked all the point systems but deep in my heart I knew that this architecture was not sustainable. In the rating systems it stated that you must leave windows open for one week to let the toxins wash out. So why are we building with them in the first place? There is also a disconnect to labour – you are sitting in an air-conditioned office, and the labourer is working hard doing two or three shifts in the sun and you don’t know how the materials work. You’re working backwards; designing the facade and choosing the materials later rather than working with the materials to see what is possible.

I realised our built environments are very ugly now and have lost a sense of identity and belonging. I think fashion and architecture have been moving in this direction together. You could be anywhere in the world and wake up in a hotel room and it could be New York, New Delhi or London. Every building is the same.

I went on a natural building course and got to see what was possible and that was where I fell in love with cob. There’s a limit to what you can learn in a workshop setting and the idea was to build something from scratch. My brother and I quit city life and moved to the mountains to take up this self-initiated project to locate something with soul and community. It was a quest of truth and beauty; how we can create spaces that feel beautiful to everyone. That was the inspiration.

Side view of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Side view of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Vanessa: How did you set about designing a house that was in opposition to mainstream architecture and education?

Raghav: It was a departure from the traditional way of designing by first sitting at a desk on AutoCAD. The site was small and moving to the mountain countryside where we had to trek with groceries every day was a big lifestyle change. We took a lot of time to study the site, seeing how the sun moves, what happened to the water when the rain came, and asking what the land is trying to say. We used to lay down on the land to feel it. It was eight months before we started any construction. We wanted the house to look like it belonged there and grew out of the land. In response to the site, we finalised the foundation and doors openings and slowly started framing the views, noting where the light came inside. The aim of the house was to instil belief in people; you don’t need to be an architect. People came with no experience and within a day learnt how to build in cob.

Participants to the construction of the Tiny Fort Farm at work. Images credit, Hanish Bhateja

Participants to the construction of the Tiny Fort Farm at work. Images credit, Hanish Bhateja

Vanessa: You speak about reinstalling belief in bioregional materials – what research did you need to do to understand vernacular materials used in the area?

Raghav: The idea is to bring desirability to these materials, so that we are not just building one cottage, we can start slowly building in the suburbs, making them mainstream in the cities. One material is not the solution; we’re looking at a palette so that we can combine solutions that are not only economically viable but timeline viable.

Existing supply chains favour fired red bricks, cement and steel. Even in such a remote place the villagers are moving towards red brick construction, despite the red bricks needing to be taken on mules, but once the bricks are there the house goes faster and is seen as a symbol of progress, building something new.

Vernacular ways are just getting more and more difficult. Even though we live in a Sal Forest which is the strongest wood to build with, we can’t use any of the wood. Even the villagers can’t take wood. They used to take slates to build roofs, but this is now banned. I understand that we shouldn’t take all the materials from this remote forest to New Delhi, which is 250 kilometres away, but you can’t deny the indigenous population their own materials palette.

It is said that the local Sal tree (Shorea robusta) stands for a hundred years, falls for a hundred years and can survive another hundred years. As we couldn’t take trees from the forest we used eucalyptus beams, another hard wood, which has become the only option as there is no ban and it’s fast growing. They say it’s more termite resistant because it has its own eucalyptus oil inside. So, we had to get our timber from outside, even though we’re surrounded by beautiful trees. We also sourced some secondhand windows from the same nearby city and the waterproofing membrane. All other materials came from 50 to 150 metres from the site including the stone. We had to locate every rock by ourselves to excavate and break the stone foundations. To carry 40 or 50 Kgs of rocks even for 50 meters is a big challenge, especially on a rocky terrain.

Participants building the roof. Image credit, Hanish Bhateja

Participants building the roof. Image credit, Hanish Bhateja

Vanessa: How did participants volunteer to come? What was the mix of local and international workers?

Raghav: We had a skilled stonemason and unskilled local labourers whenever they were in need of work. We had over 100 volunteers from 18 countries over the three years. Some people stayed for a week and some for a month, most of them had dreams of building similar projects in their own countries. We had a good time sharing stories, exchanging cuisines and dancing to different songs to make cob. Cob involves a lot of thumping and dancing and we had everything from English country songs to Indian Punjabi songs.

Vanessa: I love the fact the building process is fuelled by dancing! There can’t be any other material that you get to dance with.

Raghav: Absolutely, cob is the most fun technique because you get to dance and it’s the most democratic and inclusive. You can make it alone or in pairs or in a whole group. A five-year-old child can work on it or a frail 80-year-old person. New people brought new energy. It sounds romantic but it’s a monotonous process and we had to keep motivated through thousands of batches.

Vanessa: What are concerns people raise about building with cob?

Raghav: Mainly what happens when it rains. We had floods recently but the house functions well. If you have a good roof with an overhang and good foundations with a high plinth and you’re not building on a flood plain, the house will last for centuries.

View of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

View of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Vanessa: The house features stone foundations to increase longevity – was that an existing vernacular in the area?

Raghav: A lot of stone houses are still there but are being used as shelter for cattle as the roofs have collapsed. They used to build with stone and lime mortar, but it was a very tedious, slow process that required a stonemason to shape stone every day with the house growing an inch a day. Now there are not many stonemasons left. Vernacular doesn’t only mean materials; you have to take into account the skill set available to you. It could have been an option to go for a stone house, but the skill set wasn’t available, and we wanted to show what else is possible; how cob is a flexible material and the cognitive peace that cob can give you when you enter such a space.

Stone arch of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Stone arch of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Vanessa: The building is sheltered by a canopy of eucalyptus beams woven into the living roof – were there examples of this that you referred to?

Raghav: The major barrier to natural building is that we have not cracked robust roofing systems. One system cannot be applied to all the bioregions. Even if you have clay tiles, you don’t have proper interlocking systems available. People want convenience.

We made a reciprocal living roof which is built with a vertical ‘Charlie Stick’ supporting one rafter which in turn supports the other rafters. When the Charlie Stick is removed all the beams fall into place in such a way that they become self-supporting, like the shutter of a camera. This distributes the load and enables columnless spans. It also forms a beautiful skylight. It’s inspired by reciprocal roof maker Tony Wrench.

Reciprocal living roof. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Reciprocal living roof. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Vanessa: You speak about Mahatma Gandhi’s vision of self-sufficient villages created with sustainable practices as being the soul of India – can you see a future where Tiny Fort Farm becomes one house of many, connecting to a larger network for a collective local empowerment?

Raghav: We’re building a couple more projects in the village for a client using local construction labourers. We have hired a lot of local villagers. The most beautiful thing about cob when you’re building this way with local labourers is that it’s democratic – everyone can learn it. You see that the money from the client or your pocket is slowly dispersing, and they are building their own house or sponsoring the education of their children. The economic flow is the most beautiful part of building locally and hiring local people which is not common in cities.

The villagers are very proud there is a mud house there. We’re employing people to help us run the house. There’s an old lady that we stayed with throughout the process. She’s the cultural bridge with indigenous wisdom. She used to take us on walks through the forest. She taught us how to use every tool, how to chop straw and make chapatis. We learnt a lot from her.

View of the Tiny Farm Fort and surroundings. Image credit, Atik Bheda

View of the Tiny Farm Fort and surroundings. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Vanessa: What projects are you working on now?

Raghav: We are pushing our own boundaries with the help of like-minded aligned clients who believe in sustainability. We are trying to do new things and debunk myths surrounding natural materials and make them as mainstream as possible. We made an interior inside a concrete building and are renovating colonial houses built with lime.

As a natural builder you need to have a sense of militancy; to be a rebel and fight by-laws, alongside questions from clients and contractors as none of them have worked with these materials. We have to train contractors, but they have muscle memory and can work intuitively. They can take your techniques one step forward. It’s a fine balance to find the right mix and material.

The word we use is ‘care’; care for the planet, for the people who are building your project, for the materials and the end user. You have to take a back seat as an architect and let the site be the architect. Your role becomes that of a discoverer and enquirer who raises important questions and then sits and observes what the land is trying to say. How can you incorporate all the cultural crafts and stories that are now endangered? How can the project provide an opportunity to involve craft in a contemporary way? Care, community and conscious materials; that’s how we see our practice right now.