Scottish timber cladding company Tiny Temple is leading the way in unique and sustainable timber finishes. They are recognised as Scotland’s only producer of authentic Shou Sugi Ban, the Japanese practice of charred timber cladding. High profile clients include the V&A Dundee where Tiny Temple’s charred cladding graces the Tatha Bar & Kitchen.

ARCHITEXTURES Editor-at-large Vanessa Norwood spoke to Beren Yeshua, founder of Tiny Temple, about the almost endless possibilities of timber cladding and a business founded on the practice of meditation and the principles of lean manufacturing.

Drone shot outside of Tiny Temple's mill

Drone shot outside of Tiny Temple's mill

Vanessa: Having only been established in 2021, Tiny Temple now supplies an impressive range of beautiful cladding for well-crafted projects across Scotland and the UK. Can you tell me how Tiny Temple came into being?

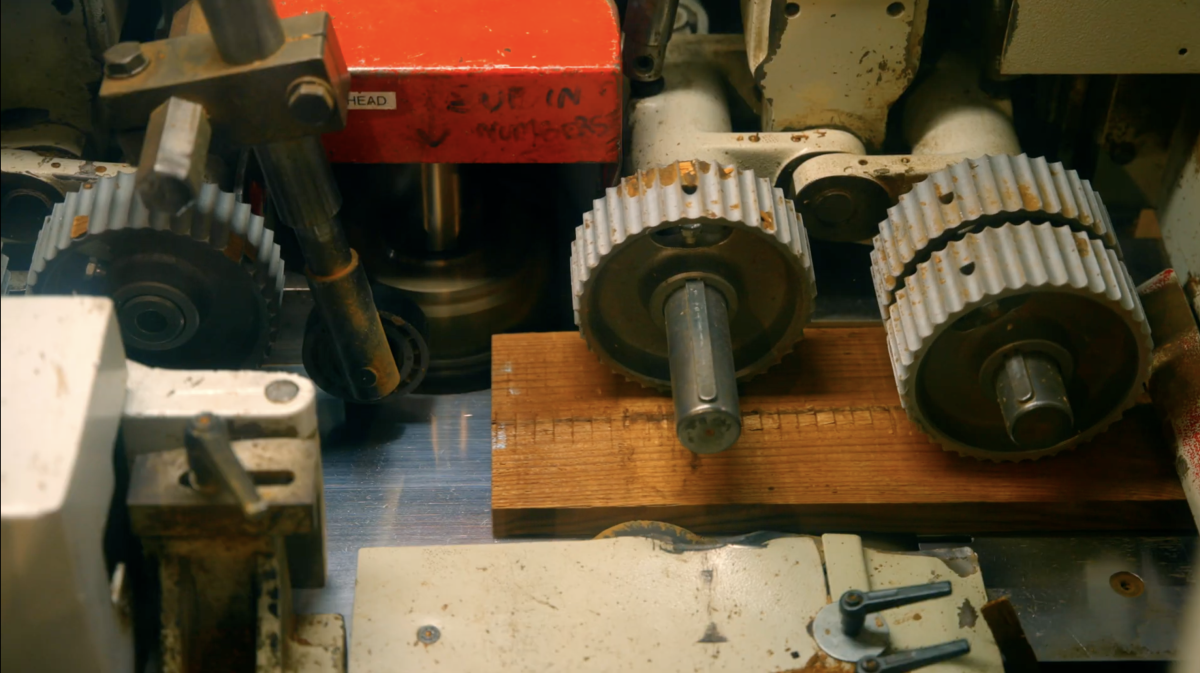

Beren: Before lockdown I had an interest in charred wood and tiny cabins. I live in a Meditation Centre in Peebles with my family and my teacher encouraged me to build a meditation hut in the back garden. I experimented with charring the cladding to see how it would go. It was slow, it took a year, but I was learning as I went. On the back of that a friend who meditates asked me to build a cabin with charred wood. I set up the company Tiny Temple based on building tiny cabins. As time went by, I thought it would be nice to make the cladding ourselves because not many people saw it as a creative process. I bought a three-and-a-half-ton four-sided planer machine at auction from a joiners’ liquidation sale in Glasgow that makes all the shapes of the cladding. You put in a rough sawn piece of wood, and it gives you the tongue and groove. We rented a farm shed and now employ seven people.

Tiny Temple employee carrying sanded timber

Tiny Temple employee carrying sanded timber

It's grown from real grassroots, and we've built up to a business where every day we're reinvesting the money, buying machinery from companies that have gone bankrupt and learning how they work, repairing and upgrading them ourselves and doing a lot of continual improvement and reinvestment here. We've kind of done everything in house and growing organically that way has allowed us to grow with stability into a successful business in a very short space of time. It's been very enjoyable and creative because we’re doing a lot of problem solving as we go. It’s been a wild ride and we're only just getting started.

Rough-sawn timber going through a planer moulder machine

Rough-sawn timber going through a planer moulder machine

Vanessa: Has your experience with meditation and a more communal way of living influenced how you run Tiny Temple as a company?

Beren: We spend 45 minutes every morning where everyone in the company reflects on what we're grateful for, what went well and what didn't go well the day before. We talk about one of the eight wastes in manufacturing (1), and we finish by stretching together. Then we go and improve the things individually, no one's told what to do so you can just go freely and improve and tidy up and clean and make it better for the day ahead. We do that every day and it's getting to be a very nice, organised place to work. It feeds into continual improvement and self-reflection. It means you can learn from your mistakes and those things that you've learned are then standardised and passed on to new people.

Vanessa: What are the processes that the timber goes through at the Tiny Temple mill?

Beren: We can burn the timber, we can also put it through machines that give it a texture like sand, or brush it to accentuate the grain, or paint it with different types of finishes and so we can bring out all the different tones and textures in the woods in different ways. We also make all the knives to make any shape, so any colour, any shape, in any species of timber. Burning the wood makes it more durable and it's been used on Japanese Temples for thousands of years. It preserves wood naturally without chemicals making it water repellent and very beautiful.

Sneak peek of the Shou Sugi Ban process

The personality of every board comes out when you burn it because every cut single piece of wood is totally unique. The growth rings of all the years of every piece of wood tells the story of the environment that it grew up in. The knots tell you which part of the tree it came from, the growth rings tell you how cold or warm seasons were. With wide growth rings the winters weren't that harsh, and you know they've grown a lot, whereas if they're very dense it's been colder. That affects how it looks when it’s burnt.

Charred timber after Shou Sugi Ban process

Charred timber after Shou Sugi Ban process

Sometimes if the larch has grown on a slope, it can bend more when you cut it because the tree holds tension trying to straighten up. You put a perfectly straight piece of wood through the machine and when it comes out it can bend because growing against the hills builds up tension in the wood.

Every timber has a unique smell. Cedar smells like heaven and Siberian larch like cardboard, and when you burn Abodo it smells just like Biscoff, the little shortbread biscuits you get with a coffee. Accoya smells like vinegar because of the process it has been through to make it long lasting, it's been pickled. You get a whole range of scents when you work with the wood.

Tiny Temple employee placing painted timber on racks

Tiny Temple employee placing painted timber on racks

Vanessa: When clients approach you what is driving their decision-making process?

Beren: It can be visual, with the colour tying in with the rest of their project, whether they want knots in the wood or a clearer appearance. Sustainability is a big factor. Whether they mind maintenance or not can dictate what kind of finish they go for. All timber turns silver after six months, some people like that and some people don't. That affects what you do. We can apply a coating that turns a very even pale grey silver, and you don't need to reapply that for 15-18 years, it looks very clean and crisp. Some people want to keep the natural brown colour, and we can apply a coating that you have to reapply every five years. We can do solid opaque colours which are reapplied every eight to ten years. Depending on where it's installed and if it's hard to reach you probably want something that’s less maintenance.

V&A Dundee's Tatha Bar & Kitchen

V&A Dundee's Tatha Bar & Kitchen

Vanessa: You work with a range of timber, where do the timbers originate?

Beren: The timber we supply from Scotland is Scottish larch. It has a lot of character, but it does have its limits, it can be bendier than other timbers and not as durable. We also sell Abodo from New Zealand which is certified carbon negative because it's fast-growing timber which has been thermally modified, it's been cooked in a kiln at 230° to make it last longer than it takes to grow. Even with the shipping from the other side of the world it saves a lot more carbon than it takes to produce. We also offer Thermally modified pine from Finland that is as durable as oak.

We’ve got the capacity and capability here to make anything. We can make totally bespoke work. We’ve got 80,000 product combinations in our system; wood species, profile styles like tongue and groove or square edge, standard sizes to almost 8-inch-wide boards, whether it’s charred or not, whether it’s got Fire Protection, whether it's painted. We get quite a lot of input on the design; it's our job to explain how that would come together and then make it happen. We're trying to base our work around making it easy for architects to get all their information and specify our products, that is where ARCHITEXTURES comes in.

Vanessa: How do you see the future growth of the company?

Beren: Going forwards we want to landscape the outside of the mill; we want to make the visit here an experience that you don't forget. Growth doesn't necessarily mean having piles of stock and a huge wasteful space. It's thinking creatively and reflecting the principles of lean manufacturing. I've always had an interest in how things work and the parts that make up something. It feels like the mill is very much like that because there's so many moving parts and they all work together in harmony to make everything happen. Because we've done everything from the ground up, everyone here has an X-ray vision of how everything happens which I find fascinating. That's the passion and the joy that I get from it. The further we go, the more I realise that with a committed team dedicated to making each day better, we can achieve anything.

Beren (centre) surrounded by his team members

Beren (centre) surrounded by his team members

(1) The 8 wastes are features of lean manufacturing; a methodology focused on improving efficiency and reducing waste. Lean manufacturing originated from the Toyota Production System in Japan which embraces a holistic and collective approach to employee engagement. The eight wastes are: Defects, Overproduction, Waiting, Non-utilised talent, Transportation, Inventory, Motion and Extra processing.

.JPG?s=1200&q=60)

.jpg?s=350&q=50)